Should the West become a proving ground for fledging carbon capture technology, or bolster conservation and land management projects that naturally sequester carbon emissions?

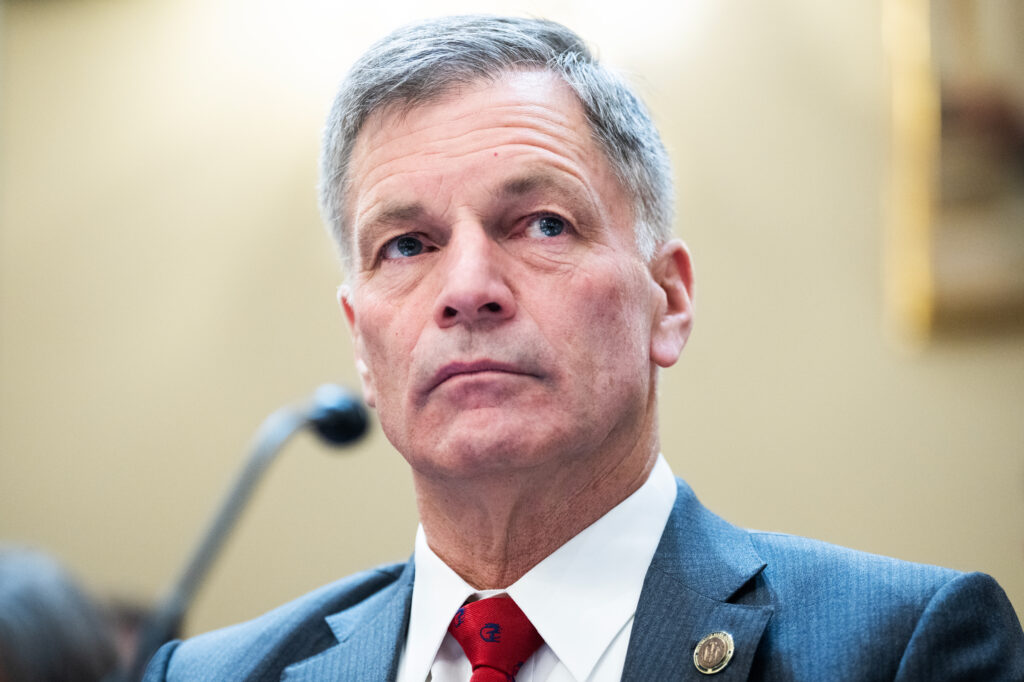

“Both” was the conclusion several Western states reached last month when Wyoming Governor Mark Gordon released a “Decarbonizing the West” report, aimed at garnering bipartisan support for ways to shrink carbon footprints. The report focused on how Western states can help pioneer industrial and natural methods of removing carbon from emissions and the atmosphere. However, it made few mentions of ramping up the transition to renewable energy to reduce carbon-loaded emissions.

The Western Governors’ Association, currently chaired by Gordon, a position that rotates through 18 other governors from states west of Louisiana and territorial governors from American Samoa, the Northern Mariana Islands, and Guam, released the report. Gordon chose decarbonization as the focus because he is “an all-of-the-above energy policy leader, focused on ensuring hungry power grids continue to be fed—for the good of his home state and the nation,” his office stated.

Decarbonizing the West proposed two pathways: high-tech approaches such as carbon capture, utilization, and storage, and natural methods involving conservation and rewilding. Technologies being developed include carbon capture from smokestack emissions and CO2 removal from the atmosphere. The natural methods would incorporate conservation, rewilding, and resource extraction projects to absorb and sequester more CO2.

These decarbonization tactics are being developed with varying degrees of urgency in Wyoming, which has invested hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars into unproven carbon capture technology while spurning clean energy funding. Despite its commitment to using nature to draw down atmospheric carbon, Wyoming has objected to federal guidelines that would elevate conservation to the same status as industrial development in public land management decisions.

Fossil fuels and their accompanying emissions, largely responsible for increasing atmospheric carbon driving climate change, were not scrutinized much in the report. Instead, Gordon shifted focus away from “curtailing the use of fossil fuels” towards strategies Western states could adopt to commodify emissions sequestration efforts.

“We should be decarbonizing by using all the technologies at our disposal to emit less carbon in the first place,” said Rachael Hamby, a policy director for the Center For Western Priorities. Hamby applauded Gordon and the Western Governors’ Association for tackling a politically and technologically fraught topic.

In the technological carbon sequestration sector, the report recommended Western states “support large-scale technology development” for carbon capture and removal, urging federal agencies to subsidize such projects to help the industry “demonstrate commercial feasibility.”

Focusing on carbon capture is not without merit, said Monika Lenninger, director of external affairs and climate policy at the Nature Conservancy. “I appreciate the focus on those technologies because they’re an important part of the picture.” She noted that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has concluded it may be necessary to develop the technology to limit Earth’s warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

“We are at a point where some of this must happen whether we like it or not.”

Carbon capture technology should be used as a last resort in sectors where emissions are difficult to eliminate, like construction, Hamby said. “The window in which we could have avoided some of these carbon capture technologies is now closed.”

While industrial approaches to carbon capture have long found a home in Wyoming, nature-based approaches have not received as much attention. That’s partly because many of these approaches do not have clear, scientifically backed methods to quantify their carbon sequestration benefits, making them difficult to monetize and finance.

To help combat the unreliable nature of the carbon offset market, the report recommended the federal government “develop innovative carbon finance mechanisms to provide upfront capital to landowners seeking to implement projects.”

But just because nature-based sequestration projects aren’t easy to monetize doesn’t mean they shouldn’t be a priority, Hamby said. “The goal is to decarbonize the West and the country to avoid the most catastrophic impacts of climate change, whether that’s profitable or not.”

One area that may benefit from being integrated into the market is wildfire management. After a century of extinguishing all forest fires, forests across the West have become “overstocked” with biomass that has little economic value. Western states and federal agencies should help create a market for biomass carbon removal and storage processes—burning timber cut from forests as part of fire hazard reduction efforts to produce energy, and capturing and storing the resulting carbon emissions—the report said.

Looking for ways to make natural carbon sequestration a profitable industry aligns with Wyoming’s attitude towards the energy transition.

“Our state is so dependent on fossil fuels. We don’t have many [tax revenue] options outside of tourism if fossil fuels continue to decline,” Leininger said. As a result, when the federal government proposes a new rule about managing lands in Wyoming, like the Bureau of Land Management’s recent proposal to elevate conservation to the same level as resource extraction, it often sparks “a lot of fear.” “I think that’s why you see that reaction, even though Wyoming people do value conservation and open spaces.”

The recommendations proposed in the report—prioritizing conservation grants for small farmers and increasing Western timber mill infrastructure—are in-keeping with initiatives already underway in the state, Leininger said.

Just days after Gordon released the report, he sent a letter to Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack expressing frustration over the U.S. Forest Service’s national old growth amendment, which would prohibit managing old growth trees for economic purposes. Recent research suggests old, mature trees are some of the best at storing CO2, accounting for about 10 percent of the worldwide emissions stored across ecosystems. However, prior to Vilsack’s announcement, the Forest Service had been criticized for selling logging concessions that allow the harvest of old-growth by the timber industry.

Original Story at insideclimatenews.org