Integrated Approaches Needed in Climate and Biodiversity Efforts

As global environmental challenges escalate, the call for unified strategies to address both climate change and biodiversity loss grows louder. Historically, these issues have been tackled independently, leading to fragmented policies with varying degrees of success. However, recent developments suggest a shift towards a more cohesive approach.

Since the 1990s, international efforts have seen climate change and biodiversity being handled through separate United Nations conventions. The UNFCCC addresses climate, while the CBD focuses on biodiversity. This division is mirrored in national frameworks, such as in the United States, where different agencies manage climate and species conservation separately. For instance, the Environmental Protection Agency deals with climate-related regulations, and the US Fish and Wildlife Service focuses on endangered species.

Globally, however, there’s a gradual convergence of these efforts. Policies now increasingly aim to create synergies between climate mitigation and biodiversity conservation. Emerging research supports this trend, highlighting the potential for “win-win” scenarios where ecosystem restoration can simultaneously sequester carbon and bolster biodiversity.

In the United States, the Biden administration’s executive order to tackle climate challenges includes conserving 30% of the nation’s lands and waters by 2030. This initiative echoes goals set by the international community under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, despite the U.S. not being a signatory.

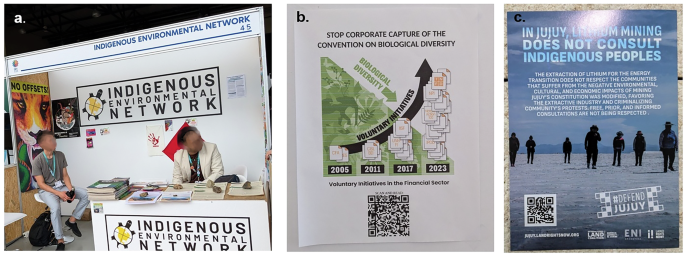

Yet, the path to integration is fraught with challenges. The CBD’s COP-16 meeting underscored the need for joint strategies, though balancing synergies with trade-offs remains a complex task. Indigenous communities, such as the Maasai, have expressed concerns over initiatives like carbon credits, emphasizing their rights and the need for informed consent on traditional lands.

Addressing these challenges requires reevaluating traditional methodologies like cost-benefit analysis (CBA), which often fall short in reconciling the complex trade-offs between climate and biodiversity. CBA’s limitations stem from its focus on quantifiable metrics, often missing the broader social and ecological implications.

Rethinking Evaluation Metrics

Climate change impacts are often measured through standardized metrics like greenhouse gas concentrations. In contrast, biodiversity lacks a unified indicator, making it difficult to equate its value against climate metrics. Biodiversity impacts are also highly localized, contrasting with the global nature of climate effects.

Moreover, while carbon reductions are fungible, biodiversity is not. This disparity complicates the development of joint carbon-biodiversity markets. Additionally, while climate science offers somewhat predictable risk assessments, biodiversity impacts, such as those from deep-sea mining, remain less understood and harder to quantify.

Exploring Alternative Approaches

Given these complexities, bioethics and collaborative governance offer promising frameworks. Ethics committees, akin to those in medical and research fields, can provide diverse perspectives and facilitate informed decision-making. By incorporating varied expertise, from environmental scientists to indigenous leaders, these committees can ensure that policies reflect broader societal values.

Successful conservation efforts in New Zealand demonstrate the potential of inclusive governance. The Kākāpō Recovery Group, which includes indigenous representation, has significantly boosted the population of the critically endangered bird.

While ethics committees could face criticism for adding bureaucratic layers, they offer a pathway to more equitable and effective environmental policies. By fostering collaboration and transparency, they can address the power dynamics that often skew decision-making processes.

Ultimately, diverse governance structures, tailored to specific contexts, are essential for navigating the intricate trade-offs between climate action and biodiversity preservation. By broadening stakeholder representation and continually refining their approaches, these committees can help bridge the gap between competing environmental priorities.

Original Story at www.nature.com