In California, New Rules Aim to Create Better Defensible Space

Mon, 2024-09-02 02:00

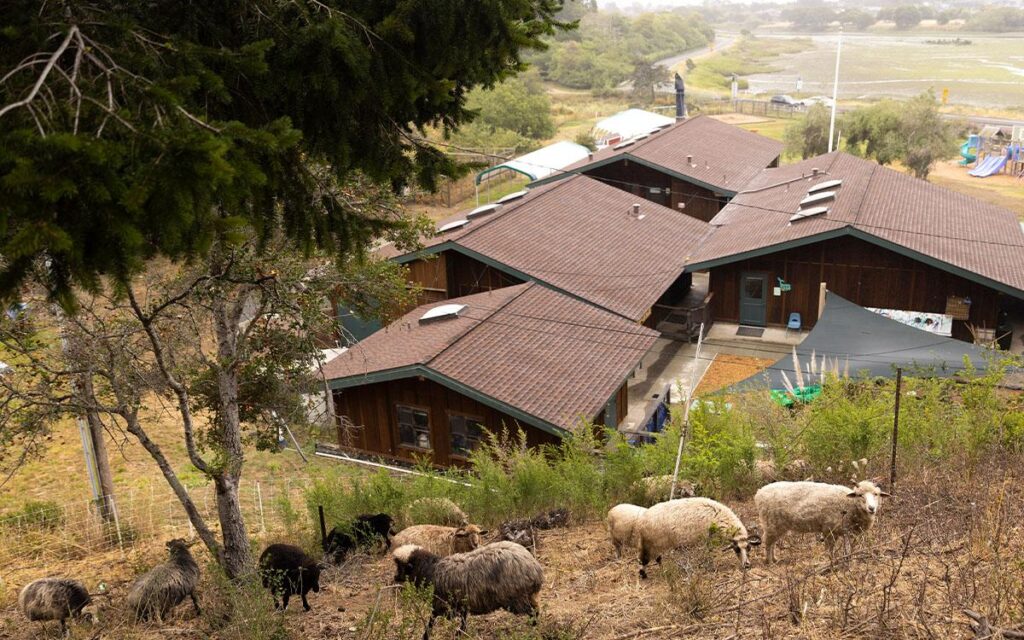

Photo by Jessica Christian/San Francisco Chronicle via AP

Suzanne Bohan

Sep 2 2024

Meghan Gaines, a defensible space inspector for CalFire, spends 10-hour shifts visiting homes in a high wildfire risk region in central California. She checks that residents follow state requirements for managing flammable material within a 30-foot zone and a 100-foot zone of homes.

Now, she’s also advising them about new state rules in development that will require an “ember resistant” zone within 5 feet of structures in fire-prone areas—with the specifics of what’s to be banned still under discussion. There will also be more intense fuel reductions in a 5- to 30-foot zone. “We’re letting people know, ‘Hey, this is something that’s coming down the pike,’” Gaines said. “‘And here are some adjustments you can start making now, before it actually goes into effect.’”

The new rules were mandated by AB 3074, a bill approved in 2020 with unanimous bipartisan votes in the state legislature and the support of 30 organizations. The bill requires the California State Board of Forestry and Fire Protection to develop rules on what homeowners in high wildfire risk areas can keep in a 5-foot zone—also called “zone zero” adjacent to their homes. “There is science behind 0-5 feet,” Gaines said. “It gives embers less footing to sit there and smolder and ignite the structure.” Research and post-fire analyses found the vast majority of homes burn during wildfires due to the accumulation of embers, which winds often carry far ahead of the flames.

Staff with the California Natural Resources Agency, responsible for writing the draft version of the rules, is expected to deliver proposed rules to the forestry board “shortly,” according to a spokesman for the agency. They’ll also be released for public comment then, he said. After the board approves a final version, the rules will apply immediately to new homes in specific high wildfire risk areas. Later they’ll apply to existing structures, with the final phase-in period decided during the approval process.

Assemblymember Laura Friedman, D-Glendale, authored AB 3074, following the most destructive conflagrations in state history in 2017 and 2018, along with the pullback of insurers offering coverage to California homeowners, citing high risks and costs. Jim Metropulos, legislative director for Friedman, emphasized that since the rules are still in development, it’s currently unknown what will be banned or allowed under state law. “The bill excludes vegetation or other fuel based on the probability that it will lead to ignition of the structure by embers,” he said. “It’s what the Board of Forestry is supposed to figure out—what they should exclude.”

Yanyao Cui – IURD/UC Berkeley

Much of the research on the key role of embers in home loss during wildfires comes from the Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety. It’s a nonprofit funded by the insurance industry to research strategies for reducing destruction from wildfires and natural disasters. In its 2023 report on mitigations for protecting homes from wildfires, the institute stated that embers flying in advance of the fire front, along with wind-blown burning ground debris, “are by far the most prevalent” threat to homes, and that “well over 90 percent of houses were ignited in the absence of direct flame or radiant heat.” Embers can ignite objects near a home, such as plants, mulch, and wooden furniture, which then spread to the structure.

The institute has developed its own guidelines for creating ember-resistant areas next to homes, in advance of the final rules from the forestry board. It demonstrates the effectiveness of that 5-foot combustion-free zone by showering two small demonstration homes with embers. One demo home surrounded by 5-foot concrete pathways and nothing combustible, withstood the ember storm with no damage. The other demo home, with plants next to walls and a wood fence attached to it, lay in an incinerated pile at the end of the test.

This new “zone zero” mandate will challenge long-held views of what’s attractive in landscaping.

“There’s definitely concern,” said Steve Hawks, with the insurance institute. “Will the aesthetics of my house still look beautiful?” Hawks is the senior director for wildfire with the organization, and previously worked for Cal Fire and the Office of the State Fire Marshal. “We have our houses with plants and wood mulch and stuff right up to the house, for decades,” Hawks said. “We really need to start rethinking what we can do in the 5 feet around our home to not only make it fire resilient, but also aesthetically pleasing.”

To tackle that challenge, his organization co-sponsored a design contest at the UC Berkeley Institute of Urban and Regional Development, offering prize money for landscape designs incorporating a 5-foot zone without plants or other combustible material. The winning plans feature hardscapes such as stone, concrete, or brick around a home’s perimeter. A common design also included “islands” of plants placed several yards back around the house, to avoid creating continuous fields of vegetation that could more easily spread fire. Another featured a mowed lawn planted with succulents set back from the home.

Kristina Hill, research director of the UC Berkeley institute, said most homes historically actually didn’t feature plantings right next to them. Planting around the base of houses was popularized in the 19th century, she said, as leading landscapers of the day sought to create “a more gracious and estate-like feel, based on English landscaping style.” She said redefining what’s attractive requires thinking “about what you really get from having plants around the house,” and if stones or other aesthetic non-combustible additions would be as satisfying.

Hill added that after taking out plants right next to her home, she found it “easier to maneuver.” She also notes that plants close to the home sometimes become so large they block light from entering, or that “junipers have turned into monsters.” She advocates designing around ecological principles, which she said means considering how wind, rain, fire, and other natural processes flow through an area. Hill said knowledge of landscapes and plants has long been an “art of survival,” and includes ensuring “that vegetation doesn’t allow fires to spread to the house.”

Casey Taylor, whose home was among the more than 18,000 structures destroyed during the Camp Fire of 2018 in Paradise, California, has no qualms following the “zone zero” guidance. She repurchased a home in Paradise, her hometown, in 2022. New homes there must meet high standards for fire resistance, following guidelines promulgated by the Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety.

Taylor meets “zone zero” standards by putting her plants in non-combustible pots and on wheels, to make them easy to move. Her outdoor furniture is metal-framed, with removable cushions. Her home earned the designation as the country’s first “Wildfire Prepared Home,” a program launched by the institute. “The landscaping looks great,” Taylor said, adding that it’s low maintenance and requires minimal water.

In July this year, with the Park Fire raging in a nearby county, the town of Paradise was under an evacuation warning to prepare to leave if needed, and Taylor just moved those few combustible items out of the 5-foot zone. Despite the evacuation warning—which was later lifted—she said, “I felt 100 percent safe, actually.”

Hill, with UC Berkeley, noted that the insurance institute offers guidelines for homeowners to follow for fire-resistant landscaping, which they can share with those they hire to maintain their land. She also said licensed landscape architects, who are responsible for public health and safety, could be consulted on fire-smart designs.

As to whether these extra steps for protecting homes will help stem the cancellation of home insurance policies due to wildfire risk, in a prepared statement the American Property Casualty Insurance Association wrote that, “attainment of the Wildfire Prepared Home designation may help homeowners improve their ability to obtain insurance.” These homes include an array of fire-resistant or noncombustible materials, along with defensible space. The association “strongly supports” the home preparedness program, it continued, and added that “consumer and community action are key to reducing losses and helping ease pressure on claims.”

For Gaines, the Cal Fire inspector, the tighter rules mean safer conditions for firefighters and increasing the odds that people will return to intact homes following a wildfire. “Anything we can do to help improve the job for the firefighters, who are risking their lives,” she said, “and to make sure that people have a home to come back to, is a step in the right direction.”

Gaines engages in post-wildfire investigations as well, and when asked what stood out in terms of witnessing defensible space strategies that saved homes, she paused for a long moment and then said, “Sorry, it’s kind of heavy. All that loss.” But, she continued, for houses still standing “it was clear that they were given good education, good information, and that they took it to heart.”

Original Story at www.sierraclub.org