Often mistaken for lifeless stones, coral reefs are vibrant underwater landscapes constructed by minuscule, jellyfish-like organisms known as corals. These structures, while static in adulthood, have a dynamic start: young corals can drift across vast ocean distances, potentially finding new, more hospitable homes.

These intricate marine habitats are essential, providing refuge and resources for about a quarter of all marine species. For humans, coral reefs are invaluable, offering over a trillion dollars annually in benefits, from coastal protection to supporting fishing industries and tourism.

However, these ecosystems are extremely vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.

The year 2023 marked the onset of the planet’s fourth mass coral bleaching event, spurred by exceptionally warm ocean temperatures. This widespread coral die-off is expected to increase as global temperatures continue to rise, according to projections.

The Ocean Agency and Ocean Image Bank., CC BY-NC

As a marine scientist based in Hawaii, I am part of a team investigating the future of coral reefs. We aim to determine if new reefs could develop at higher latitudes as tropical waters become inhospitable, while temperate regions warm. Our findings offer both optimism and concern.

Corals can grow in new areas, but will they thrive?

Coral larvae can travel vast distances on ocean currents, allowing corals to potentially colonize new areas. This natural dispersion could help relocate corals to cooler, more temperate waters, offering them a reprieve from extinction.

Bernard DuPont/Flickr, CC BY-SA

Historical data shows coral reefs have expanded in the past. However, the question is whether corals can migrate quickly enough to cope with human-induced climate change. Our advanced simulation aims to address this.

By integrating field and lab data on coral growth factors like temperature, acidity, and light, alongside ocean current patterns, we created a global model. This model considers corals’ evolutionary adaptability and range shifts to predict their response to climate change.

Our predictions indicate that coral reef migration from the tropics will take centuries—far too slow to counteract the imminent threats they face today.

Underwater cities in motion?

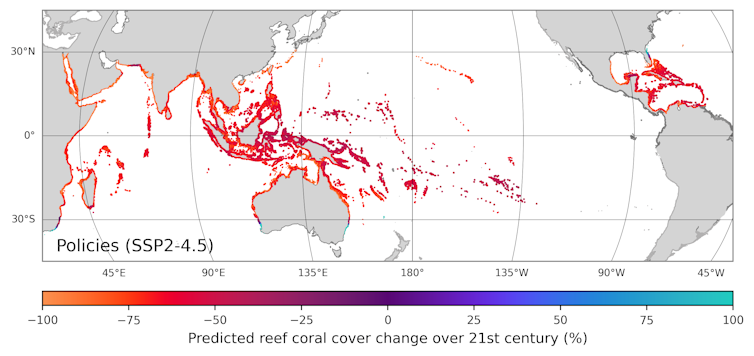

According to current global emissions policies, coral reefs could decline by 70% this century, despite being slightly more optimistic than earlier studies predicting up to 99% loss.

Some potential growth areas, like southern Australia, might see a modest increase of about 6,000 acres of coral, while about 10 million acres could be lost globally.

Noam Vogt-Vincent

Despite a predicted 25-mile-per-decade expansion of suitable coral temperatures, challenges like reduced growth rates at higher latitudes hinder coral migration.

Higher latitudes offer more variable temperatures and less light, slowing coral growth and limiting their range expansion. Although history suggests new reefs may form over time, this process could take centuries.

USFWS, Pacific Islands

Some coral species, better suited to higher latitude environments, are increasing in number. However, these corals lack the diversity and complexity of those in tropical regions.

Efforts like human-assisted migration have been used to restore reefs by transplanting live corals. Yet this method is costly and not scalable worldwide, and it is unlikely to significantly speed up coral expansion due to environmental challenges at higher latitudes.

Introducing tropical corals into new ecosystems could disrupt existing species, suggesting that rapid coral expansions may not be beneficial.

Stefan Andrews/Ocean Image Bank, CC BY-NC

No known alternative to cutting emissions

Despite the potential of coral restoration, evidence is lacking that these efforts can counteract the global decline of coral reefs.

The slow natural migration of corals underscores the urgency of reducing greenhouse gas emissions to combat climate change impacts. Aligning with the Paris climate agreement by cutting emissions more aggressively could halve the projected coral loss compared to current policies, potentially sustaining reef health for future generations.

Time is of the essence to preserve these vital ecosystems.

Original Story at theconversation.com